Brief Summary:

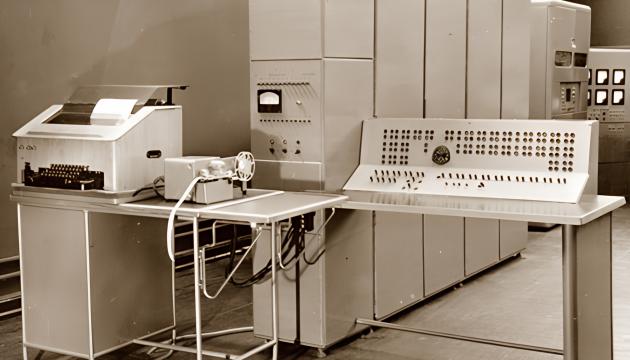

Invention/Product: Setun Computer

Developers: Nikolay Petrovich Brusentsov (lead), E.A. Zhogolev, V.V. Vereshchagin, S.P. Maslov, A.M. Tishulina, and others (Moscow State University, MSU)

Country: USSR

Period: Development 1956-1958, serial production 1959-1965

Essence: A small digital computer (EDC), unique for operating based on a ternary symmetric numeral system (-1, 0, +1) instead of the commonly used binary system.

The "Setun" was a pioneering development that demonstrated the potential advantages of ternary logic (higher information density, easier execution of certain arithmetic operations). However, it did not gain widespread adoption and development, remaining a unique experiment. The main reason for its "failure" (in terms of lack of continuation and mass adoption) was the global and Soviet computer industry's focus on the binary system, which made the "Setun" incompatible and "non-standard," as well as possible misunderstanding and lack of support from scientific officials.

Creation History

The idea of creating a computer based on ternary logic instead of binary came from Nikolay Petrovich Brusentsov, an employee of the Computing Center at Moscow State University (MSU). He believed that the ternary numeral system (especially the symmetric one with digits -1, 0, +1) could offer advantages in information density and the efficiency of certain computations. In 1956, he and a group of young engineers and students began development. The project was supported by the MSU leadership. The first working prototype of the "Setun" was ready in 1958, and from 1959 to 1965, the Kazan Mathematical Machines Plant produced about 50 of these computers.

Working Principle

The "Setun" was unique in that all its logical and arithmetic operations were based on a ternary symmetric numeral system. Instead of bits (0 or 1), it used trits, which could have values of -1, 0, or +1. This required the creation of special ferrite-diode cells capable of storing and processing ternary digits.

- Architecture: The machine was single-address, fixed-point, and serial operation. The machine word length was 18 trits (approximately 28.5 binary digits).

- Memory: Ferrite core memory with a capacity of 162 words (18 trits each), external memory on a magnetic drum with a capacity of up to 3888 words.

- Performance: About 4500-4800 operations per second (addition, subtraction).

- Peripherals: Electromechanical printing device and a photo-reader for punched tape.

A proprietary programming system, including autocode, was developed for the "Setun."

Claimed Advantages

- Greater information capacity of a trit compared to a bit (log23 ≈ 1.58 bits). This theoretically allowed for the creation of more compact memory devices.

- Simplicity of certain arithmetic operations, such as rounding numbers or representing negative numbers (no special sign bit or additional codes required).

- Potentially higher reliability of some logical elements compared to binary counterparts of the time.

- Originality and novelty of the approach, showcasing the high scientific potential of the Soviet cybernetics school.

Why Did It Fail? (Lack of Development)

- Dominance of the binary system: By the late 1950s, the global computer industry had committed to the binary numeral system. The production of components (transistors, diodes, ferrites) was geared towards binary logic. Developing and supporting a ternary component base would have required separate efforts and costs.

- Compatibility issues: The "Setun" was incompatible with other Soviet and foreign computers, complicating the exchange of programs and data.

- Lack of support "from above": Despite the successful operation of the produced machines at MSU and other organizations, the project did not receive proper support from state bodies responsible for the development of computing technology. Officials often did not understand the advantages of the ternary system and preferred more "understandable" binary analogs.

- Limited resources: The USSR could not afford to develop two different main lines of computing technology (binary and ternary) in parallel.

- Conservatism of thinking: Brusentsov's innovative idea faced inertia and conservatism from part of the scientific and engineering community.

In 1965, the production of the "Setun" was discontinued. Later, in 1970, Brusentsov created an improved version, the "Setun-70," but it was also produced only in a few copies.

Ahead of Its Time?

Yes, in a certain sense. Theoretical advantages of ternary logic are acknowledged even today. If the technology had been further developed, we might have more efficient computing systems. However, the inertia of the binary system proved too strong. The "Setun" became a bright but singular example of implementing a ternary computer.

Can It Be Revived?

Reviving the "Setun" in its original form is neither possible nor practical. However, interest in ternary logic resurfaces periodically in scientific circles, especially in the context of quantum computing (cutrits instead of qubits) or the creation of specialized processors. In the future, ternary principles may find their application in some niche or breakthrough technologies, but these will be new developments based on different physical principles, not the "Setun."

WTF Factor

The main WTF is that in an era when the whole world was confidently moving towards binary computing, Soviet engineers at MSU created and even serially produced a computer operating on an entirely different, **ternary logic**! It's like someone building a successful car powered by compressed air while everyone else was making gasoline cars. The very existence and successful operation of a ternary computer is a challenge to established norms.

According to legend, the name "Setun" came from a small river flowing near the place where it was developed, symbolizing the modesty and "invisibility" of this unique project amidst the giants of the binary era.